Sentiment: What’s in a Name?

Sentiment: What’s in a Name?

Kaan Tu

Sentiment: What’s in a Name?

Sentiment: What’s in a Name?

.

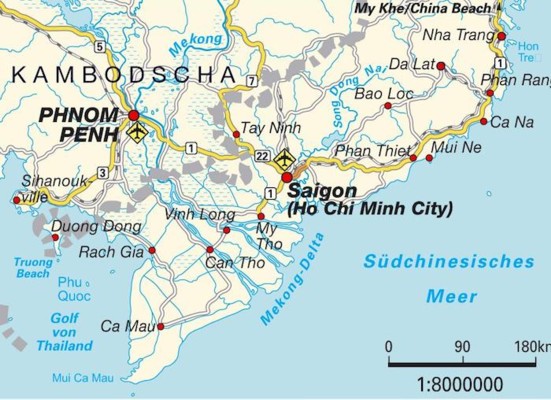

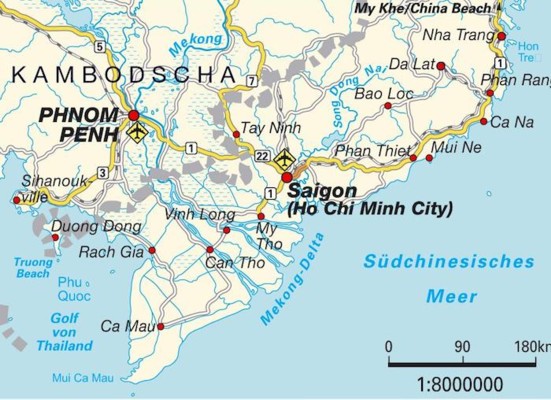

I remember when I was young, my parents used to tell me stories about Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam that shaped much of their youth. They told me about the monumental valleys, beautiful rivers connecting vast lakes, and the endless rice fields that glowed bright gold under the setting sun. To me this always sounded like a fairy-tale, a Neverland that was a far cry from where I grew up, the cold and rainy Netherlands that I eventually grew to love.

My parents gave me a globe for my seventh birthday. Every night I would spend my last waking hours searching and searching until I fell asleep, but never could I find Saigon. After months without success, I decided to consult my teacher about the mystery city. We looked it up on the brand new Google Maps, but we became none the wiser, confirming my suspicion. I was convinced my parents played me a fool and lied about this magical place they grew up in. It felt like my whole world crumbled at my feet, a feeling I would only ever again experience when I was told Santa was not real.

The following weeks I did what any child has done at least once: I decided to refrain from any communication with my family. Mom and dad soon recognised my silent tantrum, and asked what was wrong. In an outrage I yelled at them that the Saigon they told me about did not exist and that even my teacher could not find it. My parents looked at each other for moment...

“You are not wrong, son”, they said calmly, “Saigon is no more”. They then explained that when they were barely teenagers a war broke out that divided the nation of Vietnam. That very same war drove my grandparents to send their children away, to flee from a country that was falling apart, from Saigon. They ended their story with the solemn conclusion that the city they knew as Saigon was now named Ho Chi Minh City. Named after the enemy that brought the war from the North.

I was puzzled - the concept of a name changing seemed alien to me. My name was my name and that would never change right? Would Assen not always be the Assen I know? My father then told me something that I only truly understood years later: “It hurts to see something you hold so dear lose its identity and freedom. It is as if Hitler won the Second World War and changed Amsterdam’s name to ‘Hitler City’.”

When I started to look into the renaming of cities for this piece, to my surprise Saigon was not an exception in history. Far from, actually, take for example the history of how the Byzantine empire went through name changes that signified new eras, from Byzantium to Constantinople and eventually Istanbul.

When discussing these changes in history with Meindert, he posed the interesting question: “Does the name change the identity of a city, or, rather, does identity of the city change the name?”

We can see how, similar to Ho Chi Minh City, Leningrad and Stalingrad also earned their names. For the former, Petrograd was renamed in honour of the death of Vladimir Lenin, mirroring the communist mindset. In 1991 when Boris Yeltsin introduced an ‘anti-communist’ policy, which resulted in a referendum that renamed Leningrad to Saint Petersburg. A change in the countries’ mindset changed the name.

A case for how the identity change is a result of name change we can look at the history of Dutch settlers in America. New Amsterdam was established in the early 17th century and served as the seat for the government of New Netherland. In the Treaty of Breda however, England and the United Provinces of the Netherlands agreed that the English would formally withdraw from Surinam and in return receive New Amsterdam and rename it to New York. The change in ownership and name resulted in a change of population and mindset.

Ironically, I also found out that Saigon had not always been Saigon either. Before the seventeenth century, when it was still under Cambodian territory, the city was originally named Prey Nokor. Did those people feel the same way about Saigon, as my parents felt about Ho Chi Minh City?

.

Kaan Tu