Ngô Thế Vinh

Vietnam is suffering a strategic setback at the Mekong river battlefront

To the Friends of the Mekong

INTRODUCTION:

It has been 62 years since the United Nations gave birth to the Mekong River Committee [1957] and 24 years since the establishment of the Mekong River Commission [1995]. Up to the current year 2019, Beijing has completed the construction of 11 hydro-electric mega-dams (6,7) across the main current of the Lancang Jiang, the Chinese name of the Mekong River that meanders within its national boundary. Altogether, those dams account for a combined output of up to 21,300 MW. Still, that country is in the process of constructing 19 additional ones. Besides her existing dams straddling the Mekong’s tributaries; Thailand is considering a plan to divert water from the Mekong. Meanwhile, Laos and Cambodia are contemplating 12 dam-building projects over the mainstream of the Lower Mekong. Moreover, there are hundreds of tributary dams that were either already in operation or under construction all over the Mekong River Basin including the Central Highlands of Vietnam.

With the two largest dams Nuozhado (5,850MW) and Xiaowan (4,200 MW) already in full production, we can say that, as a whole, China has achieved successfully the main objective of her hydro electricity program for the series of the Lancang-Mekong Cascades in Tibet-Yunnan. As a result, 40 billion m3 of water are contained in the dam reservoirs equivalent to over 50% of the China’s contributionto the average annual river flow of the Mekong and 90% of the alluvium are likewise retained - enough for China to gain the life and death say-so over the entire Mekong River Basin.

All signs indicate that the constructions of hydro-power dams along the entire Lancang-Mekong’s current are forging ahead relentlessly. Taking into consideration the 11 hydro dams of the Mekong Cascades in Yunnan and the 4 spanning the Mekong mainstream in Laos: the Xayaburi Dam and the Don Sahong Dam completed in 2019, Pak Beng and Pak Lay Dams under construction, it is unavoidable that the countries in the Lower Mekong are turned into unfortunate victims of those dams’ immediate impacts:

1/ Northern Thailand, last July: facing the disastrous situation when a section of the Mekong was drying up, its fish dying, rice fields turning parched, the Prime Minister of Thailand was forced to issue an appeal to China to release the water from the Jinghong Dam. He also requested Laos to temporarily put to a halt the operation of its Xayaburi Dam. It is interesting to note that Thailand remains the major consumer of the electricity generated by those two dams. (4)

2/ The water level of the Tonle Sap Lake, the beating Heart of Cambodia, dropped to its lowest mark. At some places, the river showed its bed even though it was then well past the midpoint of the rainy season.Due to the weak Mekong flood pulse, the Tonle Sap River failed to reverse the flow of its current into the Tonle Sap Lake. Consequently, each year, the Cambodian people may no longer celebrate the traditional Water Festival Bon Om Tuk at the Quatre Bras in Phnom Penh.

3/ The Mekong Delta: in the current year 2019, from July to the end of August, the water originating from upstream the Mekong River proved to be so inadequate, that it caused the water at Tân Châu and Châu Đốc to drop to an extremely low level – breaking the record lowest level of the 2016 drought. Not only were fishermen deprived of their fish season but farmers also could not expect to have enough water for the coming harvest. Besides, they had to suffer a double whammy: the absence of a sufficiently strong flow of fresh water emanating from the Mekong and then also from the Tonle Sap Lake will aggravate the threat of salinization that is making deeper intrusion into the delta region. (5)

The urgent question that comes to mind is: what should the 70 million inhabitants of the Mekong River Basin including the almost 20 million in the Mekong River Delta do to adjust and survive before the situation becomes irreversible?

For almost a quarter of a century, the Mekong River Commission / MRC must have acted in connivance with the Mekong River Committee of Vietnam in the tacit

approval of the current Mekong hydro-electric projects. Vietnam is not any different. It is building hydro-electric dams on the Mekong River’s tributaries and counts among the major investor and purchaser of the hydro electricity produced in Laos and Cambodia.

In 2000, Dr. Ngô Thế Vinh published his book The Nine Dragons Drained Dry, The East Sea in Turmoil [CLCD BĐDS]. Over the years, along with the Friends of the Mekong Group, he has been doing research and relentlessly sounded the alarm about the threats facing the Mekong Basin and the Mekong River Delta. (1) In this updated article written in September, 2019 he offered this rather pessimistic observation: Vietnam is facing a strategic setback in the fight for the Mekong River while the Mekong River Delta is on its way to disintegration. Việt Ecology Foundation

STARTING WITH A STRATEGIC MISCALCULATION

Over almost a quarter of a century ago; on April 5, 1995; the Vietnamese Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Nguyễn Mạnh Cầm signed the 1995 Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin.

On that day, he committed a strategic miscalculation when he lost his country’s right to the Veto Power, a crucial provision of the 1957 Statute of the Committee for Coordination of the Lowe Mekong Basin.

Vietnam, a country located at the mouth of the Mekong River could ill afford to forego the right to protect her interests.

Summits after summits at both the Prime Ministerial and Ministerial levels have since gone by but no concrete attempt or strong voice from Vietnam has yet come to the fore while the solemnly stated mission in the 1995 Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin been ignored. No single dam has ever been stopped or rejected and the MRC Council Study is left unendorsed by its members. And it is not without reason that the Mekong River Delta has so rapidly been forced to deal with the ecological disaster we see today.

Picture 1: In 2018 PM Nguyễn Xuân Phúc led a delegation to attend the Mekong River Commission Summit. The leaders repeat the same act every four years, professing the same empty slogans. In the mean time, the Mekong River, Tonle Sap Lake, Mekong River Delta are dying a slow death. In spite of the fact that being the country located at the mouth of the river, she is demonstrably the worst victim of transboundary impacts. [photo by MRC]

Hanoi has failed to make any strong statement – especially against China or even Laos, in the defence of her interest, and the environmental flow, vital alluvium, food and fresh water security for the whole basin.

STRANGE BED FELLOWS

It is apparent deep conflicts of interest among the member countries exist. To bridge those differences we need a mutually agreed upon common denominator: The Spirit of the Mekong. Dialogues conducted in an atmosphere of open mindedness and mutual trust will help the participants to take prudent actions toward a sustainable development for the entire region.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the 1957 Mekong River Committee could not proceed any Mekong project due to Vietnam War. The Mekong River was able to retain her wilderness as well as integrity.

Then, starting in the 1970s, China, “a late comer,” rapidly introduced and implement a macro hydroelectric plan to exploit the rich hydro power potentials of the Lancang-Mekong with projects to build a series of huge hydro electric dams spanning the river’s section that runs within its borders and measures more than half the 4,800 kilometers length of the Lancang-Mekong River. The end result shows that though Beijing “came last but finished first.” To this date, China has constructed 11 giant dams on the Lancang-Mekong (6,7) that runs from its source in Tibet to Yunnan in China. So far, the reservoirs in those dams are holding 40 billion m3 of water from the Lancang-Mekong.

THE CONFLICTING POINTS OF VIEW

From the standpoint of China: From the very beginning, Beijing has declined to join the Mekong River Commission that comprises of the four member countries of Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam so that China is not bound by the rules and regulations of the 1995 Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin. In doing so, China retains absolute freedom to exploit the Lancang-Mekong that runs within her borders in complete disregard of the transboundary negative impacts that may affect all its neighbors downstream. A typical case in point: in 2016 and 2019, two severe droughts took place downstream while China cut down the flow and retained a gigantic quantity of water in the reservoirs of her dams. Recently, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned that China “taking control” of vital Mekong through dam-building spree.

The drought of April, 2016, during the duration of the drought China continued to store water in her dams, more specifically the Jinghong Dam causing the water level downstream to drop to a record level. The impacts were felt not only in the Northeast of Thailand that lies right at the foot of the Mekong Cascades in Yunnan, but also at the farthest location at the mouth of the Mekong River where almost 20 million inhabitants in the Mekong River Delta were suffering miserably due to water shortage. The rather ironic thing in all this happened when the then Vietnamese Prime Minister Mr. Nguyễn Tấn Dũng was forced to turn to China for help as he issued a call for that country to release water from the Jinghong Dam – but the belated response from China was proven futile. Clearly, Vietnam has felt a “strategic setback” that of an extremely vicious “ecological warfare” conducted by China.

The Drought of July, 2019, Once again, without warning China continued to retain water in the dams’ reservoirs right in the middle of a weak rainy season citing grid maintenance. The people in Northern Thailand experienced the drought of the century with parched fields, sections of the Mekong River baring their beds and dead fish. This time, it was the Thai Prime Minister Mr. Chan-o-cha’s turn to call on Beijing to release the water from the Jinghong Dam to provide relief to the farmers as well as fishermen of Northern Thailand. Again like 2016, China raised water level ony for a few days and cut it back again. (4)

Due to the chain reaction effect, the story did not end there. The people of the three countries Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam did not fare any better. The Tonle Sap Lake suffered an unprecedented water penury. At some place, the water was so shallow that ships went aground. [Picture 5] The more than 1.5 million Cambodians living at the Tonle Sap Delta were not the only helpless victims of the drought. People in the Mekong River Delta showed symptoms of “angina pectoris” because the heart of the Tonle Sap Lake was faced with severe water shortage.

The fallacious arguments from China: In defence of the gigantic hydropower dams in Yunnan, the hydropower engineers in China argue that the reservoirs of the hydro-power dams in Yunnan perform very useful functions: help regulate the current flow of the Mekong to benefit the countries downstream, retain the water during the High Water Season thus reducing the danger of floods from occurring downstream. When the Dry Season arrives, the same dams will discharge the water so that the river current will have more water than it normally would… such simplistic and prodam argument so far has been able to deceive a number of people – including some short sighted academics – However, reality is totally different. The Mekong Cascades in Yunnan prove to be more of a bane than a boon to humankind – not at all as proclaimed by Beijing.

Picture 2: The hydro-electric Dams on the main current of the Mekong: with just 11 dams on the Lancang-Upper Mekong, China has retained 40 billion m3 of water, produced 21,300 MW of electricity. Laos is realizing its dream of becoming “Asia’s Battery” or “The Kuwait of hydro-power of Southeast Asia”, Laos, on its part, retains 30 billion m3 of water. [source: Michael Buckley, updated 2019]

Phạm Phan Long P.E., Việt Ecology Foundation, in a recent article on VOA, observed: “Due to Climate Change, the reduction in rainfall in the basin is real but the 2019 drought has come sooner and been made more severe because of hydropower reservoir storage operation; the reservoir s operators have that ultimate ability to bring drought even in normal rain year, when there is less rain, retention of water will cause droughts more catastrophic.” (3)

…Very early on, more than a decade ago, in late May 2009, a report from the United Nations Environment Programme warned that these dams are ‘the single greatest threat’ to the future of the river and its fecundity. The new regime will largely eliminate the Tonle Sap river’s annual flood pulse, one of the natural wonders of the world, and wreck the ecosystems that depend on it.”

Aviva Imhof, former campaigns director at the International Rivers Network, said the dams will cause incalculable damage downstream. “China is acting at the height of irresponsibility,” said Imhof. “Its dams will wreak havoc with the Mekong ecosystem as far downstream as the Tonle Sap. They could sound the death knell for fisheries which provide food for over 60 million people.” (4)

From the standpoint of Thailand: aside from building Pak Mun Dam (136 MW - 1994) on the Mun River, Thailand has the plan to divert the water from the Mekong River to irrigate the ricefields in Central and Northeastern Thailand, the Thai company Ch. Karnchang provided support to Laos to build the Xayaburi Dam, the first mainstream dam on the Mekong River. More importantly, Thailand became the main client purchasing 95% of Xayaburi hydro electricity. It is necessary to add that Thailand is also the main client that purchases the electricity generated by China’s Jinghong Dam (1,750 MW) that first went into operation in 2008. That dam had a direct hand in the disaster that wrecked havoc to the inhabitants in Northeastern Thailand who had no other recourse but scream to high heaven.

From the standpoint of Laos: Laos ranks as the poorest country in the region. However, a number of Laotians saw the rich potentials for hydro-electricity generation of the Mae Nam Khong River [the Lao-Thai name for the Mekong River] as they nourish the dream for modernization. They wish to turn Laos into the “Kuwait of hydro-power of Southeast Asia” or “Asia’s Battery”. In the midst of the Vietnam War, very early in 1971, Laos built the Nam Ngum Dam (150 MW), its first hydro-power dam on a tributary. [Picture 3] Over the succeeding four decades, this country had and continues to vigorously construct a number of large dams on the Mekong River’s tributaries. Among them, we must note: the Nam Theun-2 Dam (900 MW), Theun Hinboun Dam… and at the present time Laos plans to start the construction of 9 additional dams on the main current of the Mae Nam Khong. The Xayaburi Dam is the first Domino, to be followed by the Don Sahong Dam then others: Pak Beng the third Dam is under construction, the project to build Pak Lay the fourth one has mustered past the very symbolic consultation phase. Laos will doggedly push ahead with its plan to build dams on the Mekong River’s mainstream regardless of the transboundary negative effects they create especially in the Mekong River Delta.

Picture 3: Nam Ngum, the first hydro-power dam built on a tributary by Laos in 1971 – the banderol was hung across the dam to commemorate the 25th year of Laos’ reunification [photo by Ngô Thế Vinh 2000]

China is not the only country that retains 40 billion m3 of water or 53% of the annual flow into the Lancang from China. Laos, on her part, also retains 30 billion m3 of water or 18% the average annual flow into the lower Mae Nam Khong from Laos. It is important to note the nefarious impacts the tributary hydro-electric dams built by Laos exerted on her two southern neighbors Cambodia and Vietnam whose current flow, alluvial inflow as well as fish output are seriously affected.

From the standpoint of Cambodia: Hun Sen, the longest-serving Prime Minister of Cambodia as well as of the world, has constantly refuted the destructive effects the hydro-electric dams built upstream exerted on the current flow of the Tonle Thom River (the Cambodian name of the Mekong River). Moreover, he unconditionally supported China’s plan to build the dams upstream, in total disregard of the opinions voiced by the environmentalists and inhabitants along the river.

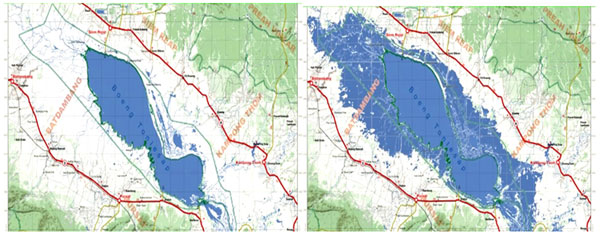

Picture 4: The surface area of the Tonle Sap Lake changes with the Dry and Rainy Seasons: In the Dry Season (left) the lake area contracts to 2,500 km2; in the Rainy Season (right), from May to September, the voluminous water current from the Mekong River causes the Tonle Sap River to reverse course and the Lake’s water level rises by 8 to 10 meters higher overflowing its banks. The flood forest becomes submerged and the Lake’s area expands five times larger to about 12,000 km2. [source: Tom Fawthrop]

Very early, in June 2005, on his way to attend the Summit Meeting in Kunming, Mr. Hun Sen expressed his satisfaction concerning the manner in which the Mekong River was being exploited. He showed no concern about it and publicly voiced his support for China’s exploitation plan of the Mekong River. Outdoing himself, Mr. Hun Sen added that the critics raised these issues merely to show they pay attention to the environment. They use their objections to impede the cooperation the six countries should offer each other. (Hun Sen backed China's often-criticized development plans for the Mekong River, AFP Phnom Penh, June 29, 2005)

Five years later, November, 2010, in the wake of the ACMECS [Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy] in Phnom Penh, Prime Minister Hun Sen again dismissed all concerns about the impacts of the hydroelectric dams located upstream the Mekong. He asserted that the cycle of floods and droughts was the result of climate change and carbon emissions that had nothing to do with the series of hydroelectric dams in China.(The Phnom Penh Post, Nov 17, 2010)

In total contrast to Prime Minister Hun Sen’s assertions, it is indispensable to record below the events that must be categorized as pessimistic pertaining to the Tonle Sap Lake, Tonle Sap River, and the Mekong River during the first decade of the 21st century:

The World Wide Fund for Nature website stated: the water level of the Mekong River has dropped to an alarming level since 2004. It has become front page news in the press: “China drains life from Mekong River – New Scientist”; “Chinese dams to blame for the Mekong drying up – Reuters AlertNet”; “Multiple dams are an ominous threat to life on the Mekong River – The Guardian”; “Blame on chinese dams rise as Mekong River dries up – Bangkok Post” . Those headlines almost unanimously point the finger at the construction of China’s hydro-electric dams on the upper river as the perpretator.

Fred Pearce, author of the book “When the Rivers Run Dry – Water – The Defining Crisis of the Twenty-First Century” published in 2006, remarked in the chapter about the Mekong River:

...“But at the end of 2003 and early 2004 was a desperate time on the Tonle Sap. The summer flood had been poor. The reversal of the river into the Great Lake started late and finished early. A five-month reversal had become a three-month reversal. Less forest was flooded, and the fish had less time to mature. The bag nets caught a mere 6,600 tons – less than half the usual haul and the worst on record… Out on the river, most of the fishermen said their catches had never been so poor. Most blame low flows. One, heading back to his floating village across the lake with empty nest, told me simply, “When the water is shallow in front of the royal palace, there are no fish in the river.”

No body can believe that Prime Minister Hun Sen did not know about that “Death knell”. Nonetheless, Mr. Hun Sen has intentionally refuted that fact due to short-term political expediency to get on the “good side” of China for the time he is still holding power. The bottom line: it is the future of the Cambodian people and the Angkor civilization that will eventually pay an extremely high price.

Picture 5: The water level in the Tonle Sap Lake drops and the boats run aground. Anh Tư Tiến has to wade into the water to lighten the load of the boat and prevent it from getting stuck on the river bed … Due to the impacts caused by the hydro-electric dams upstream, the Tonle Sap Lake is shrinking and running dry as the day goes by. [photo by Tưởng Năng Tiến]

Just recently, October 10, 2017, Prime Minister Hun Sen presided over the inauguration ceremony of the hydro-electric Lower-Sesan-2 Dam in Stung Treng. It has an output of 400 MW and its reservoir an area of 340 km2 about half the size of the island nation of Singapore. This is also the largest of the seven dams in Cambodia built by HydroLancang Company whose shares are owned by China (51%), The Royal Consortium of Cambodia (39%) and Electricity of Vietnam / EVN (10%). It is interesting to note that the electricity generated by the dam will be exported to Vietnam.

From the standpoint of Vietnam: Vietnam has been acting the dual role of making compromises and succumbing to Laos hydro-agession since 1975 through 1995 to the present. Vietnam has built reservoirs for her hydro-electric dams on the tributaries of the Mekong River in the Central Highlands like the Yali Dam (720 MW - 1996) on the Krong B’Lah River running between Kontum and Gia Lai provinces. The other dams are built on the Sesan River and Seprok River – both tributaries of the Mekong River. The Yali Dam has met with condemnation from the inhabitants of the provinces located in the Northeast of Cambodia. They blame the dams for their diminishing fish catch, the flood and loss of lives or properties of the people downstream. It is undeniably true that the reservoirs of the dams on the tributaries in Vietnam had a direct link to the water shortage that takes place in the Mekong River Delta.

A “strategy devoid of one” turns out to be the “double dealing” policy Vietnam chooses to follow. On one hand Vietnam needs water, on the other she purchases hydro-electricity generated by Laos and Cambodia. Going two steps further, through Petro Vietnam she invested in the mainstream Luang Prabang hydroelectric Project in Laos and the tributary Lower Sesan-2 of Cambodia.

In its dealing with the irrefutable negative effects those dams visited upon the Mekong River Delta: change to river discharge, loss of water source, loss of alluvia and fish... the Vietnamese government unfailingly is being manipulated by special interest groups. They did not show resolutions in opposing any dam building projects but instead agreed to invest in them. This is an action known as shooting oneself in the foot.

From the standpoint of the MRC: Since its inception 24 years ago, the Mekong River Commission was headed by a long list of executive officers – This institution has not been effectively managed as demonstrated by this observation: “the 1995 Agreement on the Cooperation for the Sustainable Development of the Mekong River Basin has fallen apart”.

In the past, the Mekong River Commission has played a rather passive hand at the renewed interest in the dam projects on the Lower Mekong. Environmentalists have called for this intergovernmental institution to assert a more responsible role regarding this issue. Surichai Wankaew, Director of the Institute of Social Research at the Chulalongkorn University, Thailand stated: “The commission needs to prove it is a useful organization for the public, not just investors”. He added that the Commission should take a new look at its duty. Instead of “facilitating dam construction, it should be a platform for affected people and society to voice their concerns.”

Prior to that, over 200 evironmental organizations and 30 nations had urged the Commission and the donor institutions to stop the construction of the dams.

A letter of protest was addressed to the Mekong River Commission and financing institutions during a meeting at Siem Reap on November 15, 2007: “We, a group of citizens, write this letter to voice our concerns about the revivals of the projects to build dams on the Lower Mekong River as well as the inability of the Commission to implement the 1995 Agreement on the Mekong during this critical time. The Commission should be in a position to prevent those dam projects from being carried out by the countries that border the Mekong. Instead, surprisingly, we only hear a dead silence.”

With the completion of the Strategic Environment Assessment / SEA by ICEM / International Centre for Environmental Management, Oct 2010, the negative economic, social and environmental impacts emanating from the dams on the main current of the Mekong have been indisputably established and made public. Many environmental organizations have joined ranks to voice their concerns about their grave and long-term impacts on the millions of local inhabitants whose livelihood depends on the water and fish of the Mekong.

Picture 6: At the Regional Stakeholder Forum for the Pak Beng hydropower Dam– Laos’ third project on the main current, organized in Luang Prabang on 2.22.2017, while talking with reporters, Mr. Phạm Tuấn Phan has strongly asserted: "Hydropower development will not kill the Mekong river. I think we need to understand that first."Certainly, Mr. Phạm Tuấn Phan would not have uttered those words if he understands without maintaining the required “Environmental Flow” all rivers will die. [Photo by Thiện Ý]

Dr. Phạm Tuấn Phan is the former CEO of the Mekong River Commission (MRC) Secretariat and a native of Hanoi.

Facing the threats of losing the alluvia and fresh water as well as the entire fertile delta gradually being submerged in sea water, the offsprings of the brave pioneers who settled the land in their Southward March just three centuries back have now become submissive. They are prevented from voicing their thoughts and shamefully forced to acquiesce to the danger of seeing the disappearance of an entire Civilization of Orchards. And in a not too distant future, on a national scale, we will witness the emergence of “ecological refugees” in this 21st century.

Recently, the science magazine Nature 2018 published a research article with the title: Potential Disruption of Flood Dynamics in the Lower Mekong River Basin Due to Upstream Flow Regulation

“The Mekong River Basin (MRB) is undergoing unprecedented changes due to the recent acceleration in large-scale dam construction. While the hydrology of the MRB is well understood and the effects of some of the existing dams have been studied, the potential effects of the planned dams on flood pulse dynamics over the entire Lower Mekong remains unexamined. Here, using hydrodynamic model simulations, we show that the effects of flow regulation on downstream river-floodplain dynamics are relatively predictable along the mainstream Mekong, but flow regulations could potentially disrupt the flood dynamics in the Tonle Sap River (TSR) and small distributaries in the Mekong Delta. Results suggest that TSR flow reversal could cease if the Mekong flood pulse is dampened by 50% and delayed by one-month.”

With Beijing as the major player who holds sway over the whole of the Mekong River Basin along with the dam building companies for the most part Chinese owned, it is expected that both the governments of China and Laos would appreciate long-held prodam view of Mr. Phạm Tuấn Phan’s and Prime Minister Hun Sen.

THIS YEAR 2019 THE HIGH WATER SEASON HAS GONE AWOL

The ageless rhythm of the Mekong River. The ecosystem of the Mekong River Delta stays in harmony with the cyclical recurrence of the “High Water Season / Mùa nước nổi” and “Pull Back Season / Mùa nước giựt”. The “High Water Season” in the Delta is a very mild affair compared to the rapidly rising floods that ravage the Northern or Central parts of Vietnam.

During the High Water Season, the water in the Tiền and Hậu Rivers gradually rises overflowing the river banks and inundates the surrounding fields. Besides washing away the acid sulphate soils and pollutants, that flood water also carries with it the alluvium, this rich god-given marvelous natural fertilizer that turns the soil fertile and renders the South into the rice bowl and fruit barn of Vietnam making it the second rice exporter in the world after Thailand.

Following the murky current rich in silt, shoals of fish swarm into the fields to spawn. When the water “pulls back”, bands of small fish swim with the flow from the fields into the canals to eventually reach the main rivers. Farmers who are not at the time busy with works in the fields stand at the ready to set up trap nets along the banks of rivers and canals. Several decades ago, the catch was so abundant that they had to open the trap nets to release some of the fish and spare the nets from being torn. (1)

Such was the past but things have changed since. Over the last two decades, that phenomenon of natural ecological balance is gradually disappearing. The “High Water Season” becomes weaker both in intensity and frequency. It cannot be attributed to “natural disaster” but rather “artificial disaster” a type of “ecological disaster” brought about by humans – and the real culprit: the Series of the Mekong Cascades in Yunnan, China on the main current of the Lancang-Mekong River. The construction of new dams in Laos will make the situation even worse.

Every year, starting in June, during the Rainy Season the flood water flows down from upstream the Mekong River to the cities and towns at the northern border of the Mekong River Delta announcing the coming of the high water that comes to a peak in about late September and early October. Sadly, this year 2019, things do not follow the usual cycle. There is even a possibility that in the near future, the High Water Season will be gone for good. As Northeastern Thailand is undergoing the drought of the century, satellite photographs show that the water level of the Mekong River at the Golden Triangle has dropped to a record low.

Picture 7: Life activities during the “High Water Season” 2000. The farmers feverishly set trap nets to catch fish along the canals. The flood water washes clean the fields and brings with it the alluvium with the promise of a plentiful planting season. [photo by Ngô Thế Vinh]

Reporter Bình Nguyên, of Cần Thơ Magazine Online August 4, 2019 stated: “in the waning days of July, 2019 we traveled along the country’s borders at An Giang, Đồng Tháp. Normally, at this time in previous years, the flood water has fully submerged the fields, farmers were busy catching fish... Now, at the same site, we only see parched fields, boats lying forlorn on the mudflats.” (5)

Nguyễn Hữu Thiện, an independent expert of the Mekong River Delta ecosystem, noted: “On an average year, the Mekong River records a total water flow of 475 billion m3. Of that total, rainfall at the Mekong River Delta only accounts for 11%. Consequently the water in the Delta depends mostly on the inflow from upstream. When there is less water in the Mekong basin there will be a corresponding decrease in the water in the Mekong River Delta. Consequently, the High Water will register a low peak in mid October in the Delta followed by a deeper intrusion of seawater in around March, right after the Tết Festival”

“Past experience shows that there are not many measures one can take to deal with extreme droughts like that of 2016. The efforts to build dikes to defend seawater intrusion will avail to naught if on the inside dike or the Delta there is not enough fresh water that needs that protection … This year when the flood water does not come, the fish source will diminish, the livelihood of the people who depend on it will naturally suffer. After one year of drought on that scale even if the flood water returns during the following year the fish output will still remain low because the fish do not have enough time to recover”- Mr. Thiện added. (5)

According to Dr. Lê Anh Tuấn, Vice Director of the Research Institute on Climate Change, Cần Thơ University, the water level of the Mekong River in the Mekong River Delta is low compared to previous seasons. This is an indication that the High Water Season in the following year (if it comes) will be very weak. It will bring a diminishing alluvium content, a shrinking fish source, inadequate fresh water to contain the intrusion of brackish water also to wash away the acid sulphate and impurities in the soils. By the same token, the production of rice and fruit trees will also be affected. The solution is to minimize the area used for rice cultivation, preserve as much rain water as possible…on top of that select fruit trees that require less water to plant.” (5) [End of Quotes]

With an inadequate supply of fresh water, in the near future, the Mekong River Delta will cease to be the rice bowl and the country can no longer rely on that very important food source. What will happen then to a country that only two decades ago ranked as the second rice exporter of the world after Thailand?

A SPIRIT OF THE MEKONG RIVER: NEW CEO OF THE MRC

Dr. An Pich Hatda , an alumnus of the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT), has been appointed Chief Executive Officer of the Mekong River Commission (MRC). He assumed office on January 18, 2019. Dr. Hatda is the second person from a riparian country to hold this position. He replaces Dr. Pham Tuan Phan of Viet Nam. Dr. Hatda earned a Master’s in Agricultural Systems from AIT in 1997, after which he completed a doctorate in Development Studies from the University of Tokyo.

During these extreme and trying times, this news can be compared to a welcome fresh breeze. Dr. An Pich Hatda is known for his managerial skill for 2 decades in the MRC.

Figure 8: MRC Secretariat, hold first dialogue with Save the Mekong Coalition. The meeting, held at the Secretariat in Vientiane on March 19, 2019 aims to create a better understanding between the two parties and to exchange and update on various Mekong development issues, with an ultimate goal to initiate a possible future collaboration between the two. Dr. Hatda standing, sixth from the left, Trinh Le Nguyen, PanNature VN second from the left. [photo by MRC]

It is hoped that with his wealth of experience gained over the years at the Mekong River Commission, Dr. An Pich Hatda would be well placed to command a good grasp of the critical issues affecting his organization and that he would be able to effectively steer his ship safely through the turbulent and divisive waters of present day’s geopolitics.

After having been in operation for 24 years (1995-2019), the Mekong River Commission bequeathes to its new CEO these two immediate challenges and a long-range one:

To overcome and succeed in meeting the above challenges will not only be a personal achievement for Dr. An Pich Hatda, but it also means living up to the “raison d’être” of his position and also of his institution which bears the name the Mekong River Commission.

The livelihood of about 20 million inhabitants of the Mekong River Delta, the food security of the entire nation, the civilization of rivers, the ecoresources of the South are all being ruined. What is the cause of that tragedy? To point an accusing finger at the dams upstream is justified! Yet, how can we ask those countries to put an end to their actions when Vietnam is also building dams on the tributaries of the Mekong River on its territories? When Vietnam takes part in funding Luang Prabang, the largest dam building project in Laos? When Vietnam chooses to purchase electricity generated by those dams and issues halfhearted protestations meanwhile? When Vietnam did not bring a lawsuit against Laos before the international court? Considering all the above points, Vietnam has suffered a strategic setback, has given up on the Mekong River Delta in exchange for the above-mentioned short-term benefits.

In 2019, the Big Drought of the Century sounded the alarm bell for the entire basin to remind the people that now is the time to mend their differences, rebuild their trust. There already exists a Regional Agreement. The crux of the problem is how to make the governments that signed the 1995 Agreement to observe its articles not only with the purpose of protecting their national interests but going a step further to cooperate in the “Spirit of the Mekong” as a common denominator for common development on the march toward common prosperity and regional peace.

Ngô Thế Vinh, M.D.

California, 11/09/2019

(From: vietecology.org)

__________

References:

1/ Đọc tác phẩm Cửu Long Cạn Dòng, Biển Đông Dậy Sóng. Đỗ Hải Minh, Tập san Thế Kỷ 21, Số 139, 11/ 2000. Mekong Dòng Sông Nghẽn Mạch, Ngô Thế Vinh, Nxb Văn Nghệ 2007.

2/ Potential Disruption of Flood Dynamics in the Lower Mekong River Basin Due to Upstream Flow Regulation. Yadu Pokhrel, Sanghoon Shin, Zihan Lin, Dai Yamazaki & Jiaguo Qi , NATURE 2018 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-35823-4

3/ Mekong: Trận “hạn hán thế kỷ” nhìn từ quan điểm hạ lưu. Phạm Phan Long, VOA 25.07.2019 https://www.voatiengviet.com/a/mekong-tran-han-han-lich-su-ha-luu/5013842.html

4/ Prayut: China, Laos, Myanmar asked to release water. Mongkol Bangprapa, Bangkok Post 24.07.2019 https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/1718087/prayut-china-laos-myanmar-asked-to-release-water

5/ Đầu nguồn “khát nước” và những nỗi lo. Bình Nguyên, Báo Cần Thơ Online: 04.08.2019 https://baocantho.com.vn/dau-nguon-khat-nuoc-va-nhung-noi-lo-a111866.html

6/ Việt Nam phải mạnh mẽ đối với các nước thượng nguồn Mekong dù đó là nước nào?! Thanh Trúc phỏng vấn Brian Eyler, tác giả cuốn những ngày cuối của dòng sông Mekong Vĩ Đại, 2019-08-01

https://www.rfa.org/vietnamese/video?v=0_gx0108ik

7/ Damming the Mekong Basin to Environmental Hell. BRAHMA CHELLANEY, Project-Syndicate, Aug 2, 2019 https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-dams-mekong-basin-exacerbate-drought-by-brahma-chellaney-2019-08