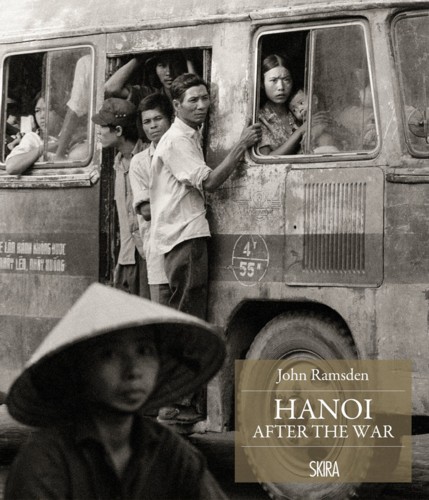

Hanoi After the War

About the Author

John Ramsden lived in Hanoi from 1980-82, as part of the British Embassy.

He spent the rest of his career in Europe.

His photographs of Hanoi were the subject of an exhibition in 2013 (in London and Hanoi).

He is now retired and divides his time between London and France.

***

Contributors

Dương Trung Quốc – preface and captions

“Workers at a rice mill on Đào Duy Từ Street, site of the old rice market. there were millers here right up to the time of ‘socialist reform’, when their machinery was collectivised. These could be ordinary workers in their ragged clothes and dust masks but they might also be ‘reformed capitalists’ hiding their faces. My aunt was in this category and also worked here.”

Born in 1947 in Hanoi’s old quarter, the historian Dương Trung Quốc is member of the National Assembly for Đồng Nai, General Secretary of the Vietnam Historians’ Association and Editor-in-Chief of its monthly review XưaNay (Past & Present).

***

Andrew Hardy – Editor and afterword

“In upside-down Hanoi, the better-off kept pigs, the middling sort bred chickens and only the very poor had no animals in the kitchen. Those leaving for Soviet factories to pay the country’s war debt with their labour kept their departure secret, for fear of others’ jealousy. People pressured to move to new economic zones signed forms stating they were volunteers. Entrepreneurial sorts invested in risky boat passages to Hong Kong and Southeast Asia.

All these worlds appear in this book’s photographs, captions and essays”.

Andrew Hardy, born in the UK in 1966, is professor of Vietnamese history at the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (French School of Asian Studies – EFEO) and head of the EFEO’s centre in Hanoi.

***

Nguyễn Quang Thiều – “Dark Shadows in our Houses”

“Bicycle spokes sold well. They made good gifts, too: after a trip abroad, people might give ten spokes to a relative or friend. When their spokes had broken and they couldn’t afford new ones, people replaced them with sticks of bamboo. It made for a bicycle unique to Vietnam.

I remember the story of Mr Hồ Giáo, a villager who was twice named Labour Hero.Three years after the war ended, he returned to the South to visit his home village in Quảng Ngãi, taking precious bicycle tyres as presents. His relatives were astonished and amused: such things were easy to buy in the South. But in the North, tyres were distributed through the rationing system... ”

Born in 1957 at Làng Chùa near Hanoi, the writer Nguyễn Quang Thiều is known for his poems, short stories and novels set in the northern countryside. Several of his works have been translated, including The Women Carry River Water (1997). He is Vice-President of the Vietnam Writers’ Association.

***

Phạm Tường Vân – After the Bombs Were silenced

“I was born on the edge of a bomb crater. The moment I greeted life was marked by the sound of sirens. My mother tells how in the rush to get down to the bunker, there wasn’t time to issue numbers for some of the new-born. When they came up, the babies were handed out to their mothers like loaves of bread. My mother had no chance to check if I was really her daughter.

One lunchtime she returned from the factory, dashed into the house, knocking over her bicycle and hugging us tight as she burst into tears: “The war’s over!”

Born in 1972, Phạm Tường Vân grew up in Hanoi’s colonial quarter. She moved to Ho Chi Minh City in 1997, where she works as a screenwriter, poet and journalist.

***

John Ramsden – Photographs and Introduction

“When I finally went back, it was to a place transformed. The Hanoi that I had known—a subdued and sad place, though of wistful beauty—was now a booming modern city.

This is a journey back to that earlier time, to a city exhausted by forty years of war. My photographs show, I hope, how fascinating I found the city. But what was it really like for its people? That, I could only guess: any meaningful contact was forbidden in those Cold War days. The essays and captions take us into the inner world of the people whose way of life is recorded here: bitter-sweet memories of a time that now seems vanishingly distant”.

Born in 1950, John Ramsden lived in Hanoi from 1980 to 1982, when he was Deputy Head of the British Embassy. He spent the rest of his diplomatic career in Europe. His photographs of Hanoi were the subject of an exhibition in 2013. He is now retired and divides his time between London and France.

***

Trần Trọng Kiên – Foreword

“I was very pleased to be able to support John’s exhibition in 2103, which brought young people face to face, mostly for the first time, with how their parents and grandparents coped in those post-war years. For those who lived through the period, it brought back powerful memories, both of hardships overcome and of the strong spirit which helped us all to survive such a difficult time.

It is a story that deserves to be known outside Vietnam. I am delighted that John’s work has culminated in this beautiful book. These photographs, together with the memories of writers from my country, are both an historical record and a faithful portrait of a remarkable time and place. It reminds us how much has changed in such a short time, but also captures the things that have not changed: the spirit of our people, the beauty of our country, and the enduring strength of our culture”.

Trần Trọng Kiên is the Founder/Chairman and CEO of Thien Minh Group (TMG), an integrated travel group specializing in the Southeast Asian region. He originally ran local tours to fund his medical studies and since then TMG has grown into a leading global company. Kiên is also a board member of the Asia Commercial Bank, Vinaland Limited, and Fulbright University in Vietnam.

***

Vũ Thị Minh Hương – My Younger Days

“We did our daily family cooking in a collective kitchen, using firewood and sawdust as fuel and sometimes even dried khaya tree leaves. Every afternoon after finishing our homework, we’d all go and sweep up leaves in Nguyễn Cảnh Chân Street and Hoàng Văn Thụ Road, where there were many leaves and few passers-by. We stuffed the leaves into bags, dragged them home and dried them in the yard outside the housing block. Only later did oil become available, and after we started using oil fired stoves we felt that life was becoming a bit more modern and comfortable….

… Each family had 20 to 24 m2 to live in. The space under the bed was packed full of precious firewood, bought with ration coupons and carefully stored as even the loss of a small piece had an impact on the family’s cooking”.

Born in Hanoi in 1960, Vũ Thị Minh Hương trained as a historian and worked in Vietnam’s national archives, serving as Director General of the State Archives and Records Department until 2015. She is Deputy Chair of UNESCO’s Memory of the World committee for the Asia-Pacific and Vice-President of the Vietnam Archivists’ Association

***

The photographs in this book were taken in Hanoi and other parts of Vietnam by John Ramsden, who was deputy head of the British Embassy in the early 1980s. When his posting in Hanoi came to an end, he set off for other capitals, mainly in Europe. The photographs – taken as personal souvenirs – were put away in a cupboard.

Thirty years passed and John Ramsden retired. He dug out the photographs, wanting to look back on his time in Asia. He shared them in an exhibition at the Museum of East Asian in Bath (2010). Then, with support from the Vietnamese community in the UK, an exhibition in London in spring 2013 established the collection’s reputation and it was not long before the photographs returned to Hanoi, allowing the city’s people to contemplate their own image of thirty years before.

For the exhibition held there in autumn 2013, the author chose an emotionally charged title, Hanoi: Spirit of Place. I was fortunate to be asked to write the captions for the photographs that were exhibited and published in a modest catalogue.

For me – a resident of Hanoi who lived through the same circumstances at the same time as the people in the photographs – when I ‘read’ these images, I see them as part of my own personal set of memories. The photographer’s talent and the miracle of technology have ‘given eternity to a glimpse’ and turned each press of the shutter into a recorded slice of past reality, a stopping place for memory. If history can be seen as the linking up of a community’s memories, then these pictures are historical documents that bear honest and living witness to a dramatic time in the past of Vietnam and its capital Hanoi.

For the Vietnames portrayed here, reunification, gained through a long struggle, was still fresh with the hope of peace; but instead of peace, the country found itself steeped in gloom and confronted by a set of new, violent and tragic challenges. Two fronts of a decade-long war were established with former allies, on the borders to the southwest (Cambodia) and north (China); the USA had withdrawn from the war but maintained an embargo; the West, including the UK, had established diplomatic relations but remained indifferent and suspicious towards a Vietnam that was facing off the genocidal regime of Pol Pot in Cambodia. The war and the embargo left the country’s economy in a state of exhaustion. Its society was unstable because of weaknesses in governance, with refugees leaving the country in droves, and many other signs of a full blown crisis.

It was not easy, at the time, to record the realities of a country that remained emotionally in a state of war.

In 1982, Trần Văn Thủy made a film called Hanoi Through Whose Eyes (Hà Nội trong mắt ai) to record the emotions of Hanoi’s people, faced with the historic challenges of the period. The film was banned for a while, its talented and courageous director vilifed as someone who sought ot hummiliate the regime. This was perharps the result of a shallow understanding of the film, one that saw only its melancholy side but missed the expression it gave to the peole’s vitality, patience and belief in the future. Later the country’s leaders lifted the ban and retrieved the film from this narrow reading: it then became symbol of Vietnam’s self-transormation that started in 1986 with the Đổi Mới reforms.

For this reason, when John Ramsden shares his personal memories – whether the pictures are of people or scenery, whichever corner or alley of Hanoi they are taken in – we sense their dramatic quality. We sense the emotion of ‘optimism amidst tragedy’ of a people and of a city that went through painful sacrifice and tireless struggle for those things that today, thirty years on, are appearing on the streets of Hanoi and throughout Vietnam, as the reforms take their course.

Most of the pictures are of everyday activities in the lives of ordinary people, with one exception. This is a face that also appears, not by coincidence, in the film directed by Trần Văn Thủy. For many Vietnamese the face of the painter Bùi Xuân Phái – famous for his deeply evocative paintings of the streets of Hanoi’s old town – symbolises that period in the city’s history. Looking at this photograph, it occurred to me that perharps the experience of talking to Phái and looking at his work found its way into John Ramsden’s pictures and helps account for their sensitivity to the spirit of Hanoi at that time.

Dương Trung Quốc